Economic Outlook 2025: Three Yards and a Cloud of Dust

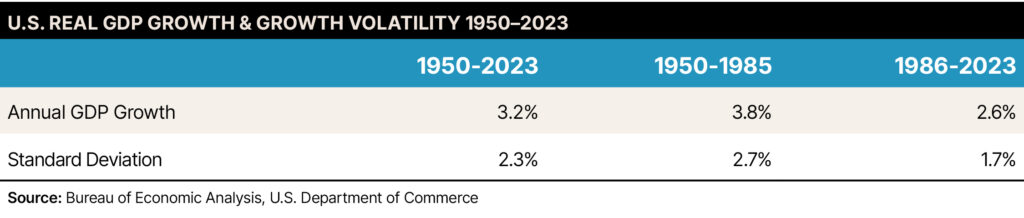

Since 1950, the average annual growth rate of U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) has been 3.2%.1 But as most are aware, the economic growth hasn’t been at a sustained 3%+ level for quite some time. Over the last 20 years (2004–2023), GDP growth has exceeded the longer-term average only three times (2004, 2005, 2021)2. 2024 will prove to be another year of subpar economic growth. We suspect that 2025 will follow suit.

While we worry over our seemingly low secular growth rate, consider the major developed economies outside of the U.S. According to a recent article in The Economist, over the past three decades:

- The U.S. economy accounted for about two-fifths of the GDP of the Group of Seven (G7) countries in 1990. Now it makes up about half.

- Economic output per capita is about 30% higher in the U.S. than in Western Europe and Canada and 60% higher than in Japan, output gaps that have almost doubled since 1990.

- In Mississippi, the poorest U.S. state, residents earn on average more than Brits, Canadians or Germans.

Many bemoan the problems that we Americans face, but in relation to the rest of the globe, the U.S. economy is a marvel. Per the article in The Economist, the U.S. economy is “The Envy of the World.”

2025 Economic Outlook

From 2004–2023, GDP growth has averaged 1.9%3. I took the “under” stance in 2024 and continue to do the same for 2025. We are forecasting the U.S. “real” economic GDP growth rate will fall in the 2.0% to 2.5% range for 2025. While positive, growth should continue to be slower than the long-term average of 3.2%4.

This lower-than-normal growth rate has been driven by many factors, including demographics (the nation’s population is getting older), a significant rise in government spending (which as a percentage of GDP has risen over the last 20 years) and consumption preferences. I argue these factors lead to a continuation of the “Three Yards and a Cloud of Dust” economic theme—slow growth and low inflation pressure.

U.S. Economy Recent Record

When answering the question “What is U.S. real GDP going to do in 2025?”, I have to start with a view of where the economy has come from and where we currently stand. As noted in the instructive chart above (U.S. Real Gross Domestic Product (GDP)), we can see the shape and record of U.S. real GDP growth going back to 1950. Consider the U.S. GDP growth and volatility track record since 1950:

The economy shifted secular growth gears starting in the mid-1980s as compared to the previous 35-year period. Real growth and growth volatility have been significantly lower than in earlier years. I suggest this major change has not been due to happenstance. Something started taking hold in the mid-1980s that created lower growth and less volatility in economic activity growth than had been the case, and those changes remain in place today.

Another observation is attached to the first in that recessions have become less frequent than was the case in the 35 years leading up to the mid-1980s. Prior to the mid-1980s, recessions tended to occur every five to six years. Since then, recessions have occurred about every eight to nine years. The extension of the business cycle was occurring. Why did these major macro-events occur? My work shows that this significant downshift in growth has occurred for many reasons, but the three that stand out are changes in demographics, government spending and consumption preferences.

Consumption Preferences

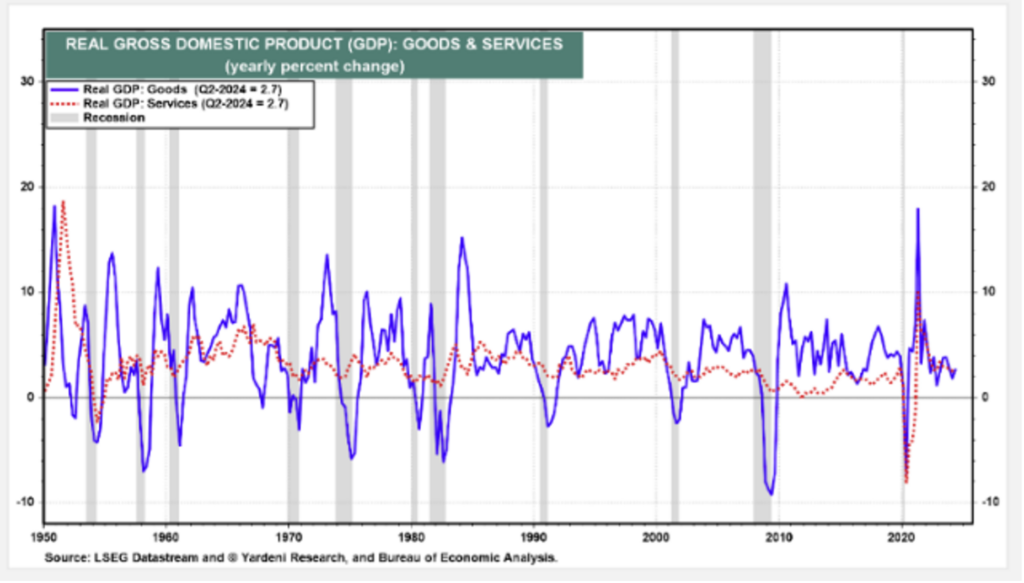

We can start the answer to the question by looking at the next chart (Real Gross Domestic Product (GDP): Goods & Services), which shows, on a comparative basis, the volatility of spending on goods versus services over the same period with the same format—a historical road map of consumption preferences. Note how little volatility there historically has been in services spending (red dotted line) as compared to spending on goods (blue line). Consumers spending more on services rather than goods has occurred hand in hand with lower economic growth and less growth volatility.

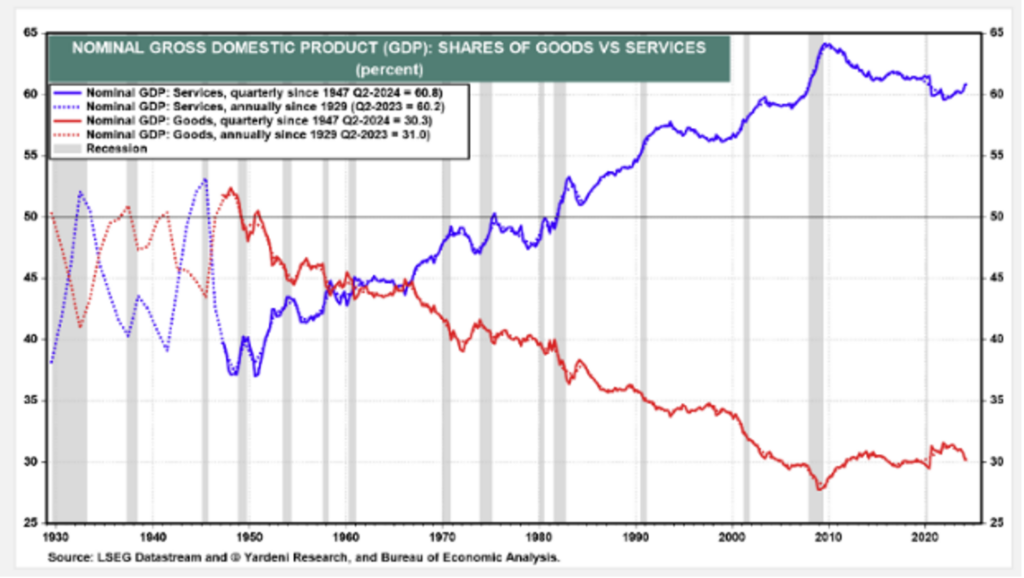

Next, we look at how much people are spending on services versus goods (consumer preferences). The second chart (Nominal Gross Domestic Product (GDP): Shares of Goods vs. Services) shows the history of those preferences. Note that prior to the mid-1960s, consumers spent more on goods than on services. Since then, this preference shifted as consumers started spending more on services versus goods, which brought less volatility to consumption spending patterns on a systemic basis. Oh, and by the way, as people age, the percentage of their budget allocated to services grows in relation to spending on goods.

Demographics

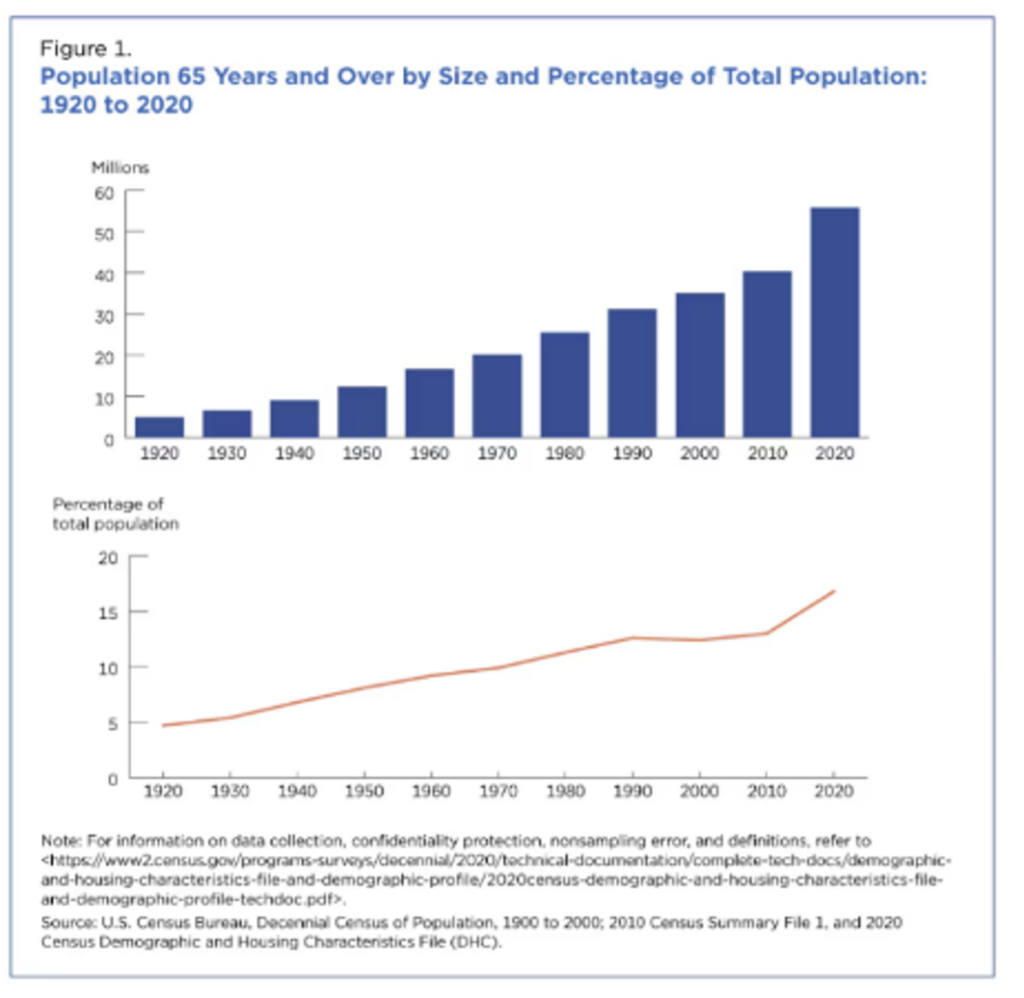

Old people retire and produce much less than they did when working, if anything at all. As noted in the chart here (Population 65 Years and Over by Size and Percentage of Total Population), 16.8% of the U.S. population is 65+ years old. Over the recent 10 years (2010–2020), the number of 65+-year-olds increased from 40.3 million to 55.7 million people, an increase of 38% in only 10 years. This demographic has injected economic drag in that these folks aren’t producing much. But their consumption rates tend to be fairly steady, leading to slower but sustainable growth rates.

Rise in Government Spending

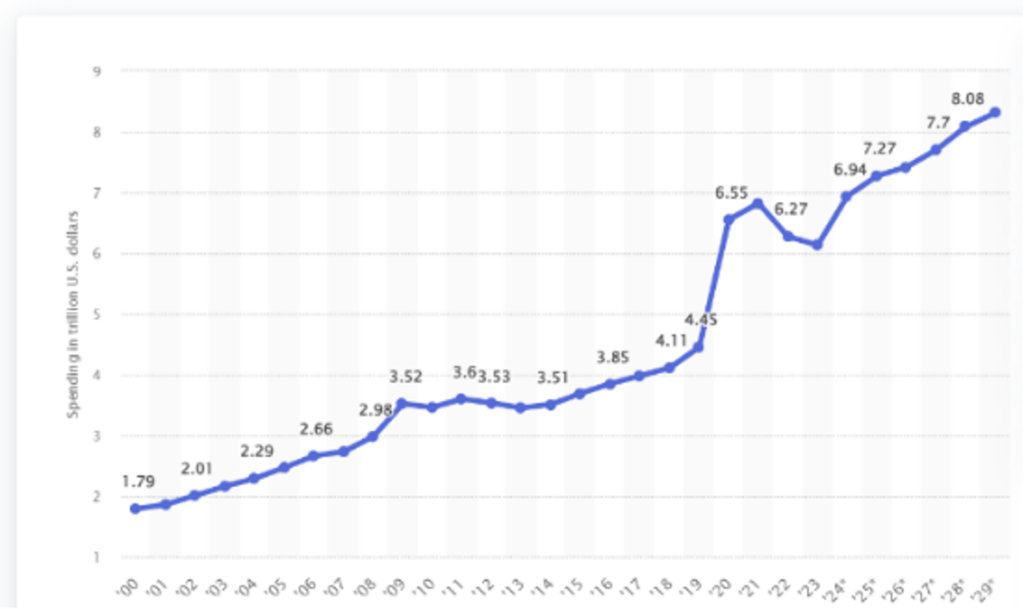

Like it or not, the government has become much more important to (some would say intrusive in) the nation’s economy due to ever-increasing spending levels. As the chart below shows (Spending in U.S. Dollars 2000-2029), from 2000 to 2024 federal government spending grew from $1.79 trillion to $6.5 trillion, an annual increase of 5.6%, while the economy grew by 4.4%. Over the noted 24-year period, government spending increased by 33.1% more than nominal GDP growth, per the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). Additionally, it is important to understand that government spending isn’t driven by supply/demand constraints as much of the competitive market. Politicians will spend money irrespective of the economic environment. Indeed, they may spend more during times of building economic stress. Unfortunately, they haven’t reduced spending during times of strong growth.

Spending in U.S. Dollars 2000-2029

Prior to the spending explosion brought on by the COVID pandemic, government spending was 15% to 20% of nominal GDP, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Forecasts from the CBO suggest government spending will be 25% of GDP in 2024, a ratio that historically has been reached only during times of war or economic emergency. As a result, government spending activities weigh more heavily on macroeconomic variables now than has been the case historically. Government spending acts as a smoothing agent for economic growth. Unfortunately, it can act as a depressant on growth as well.

Good Government Spending vs. Not-So-Good Government Spending

It makes sense to understand how much money politicians want to spend and on what they want to financially support. From an economic standpoint, there is “good” government spending, which enhances macroeconomic growth rates, and “not so good” government spending, which, while perhaps socially desirable, does not add to overall growth. As noted above, federal government spending has increased by 5.8% annually over the last 24 years (see chart above, which depicts total federal government spending from 2000 to 2029).

Over the last 24 years, analysis by the CBO shows that spending on defense grew by an average of 4.8% annually and spending on interest coverage grew by 6.0%. Leading the spending parade was “Human Resources,” by far the largest segment of government spending, which grew by 6.3% per year, or by 331% since 2000. Most of the “mandatory” spending bucket—the largest category in the government’s budget—are programs that move money from one segment of the economy (taxpayers and lenders) to others who receive government checks for various reasons, including spending on education, social services, health, Medicare, Social Security, income security and veterans’ benefits (the largest being Social Security).

While viewed by many as socially desirable, most of the spending in this area, which represents about $2 out of every $3 spent by the government, can be viewed as economically neutral to negative. This type of spending tends to be associated with very low economic “income multiplier” effects, according to research from Dr. Robert Barro of Harvard University. While acting as a growth depressant, this type of spending smooths economic fluctuations. When measured as a percentage of GDP, from 1974 through the CBO’s projection for 2034, mandatory spending has increased/will increase from less than 10% of GDP to around 15%.

In summary, government spending has become much more important when considering our economic outlook than has been the case in the past. Most government spending creates little, if any, real and sustainable economic growth—and may indeed create economic drag and risks.

Worker Productivity and Inflation

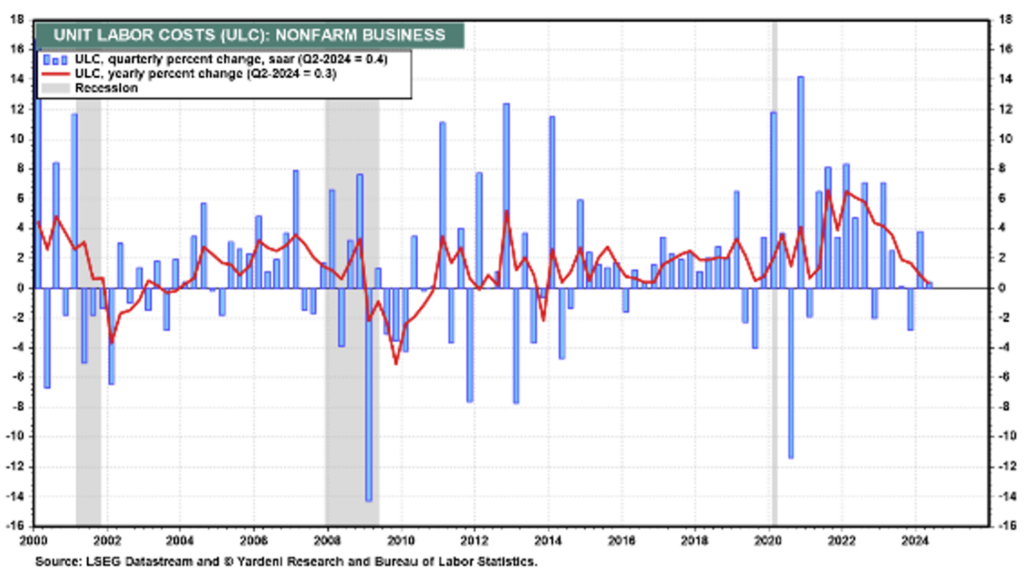

So, what of inflation? Will inflation rates continue to fall in 2025 akin to 2024? According to the St. Louis Fed, inflation has fallen from almost 9% to the mid-2% level. What are the catalysts present that may help maintain low inflation rates and add to further inflation improvements? Let’s talk about worker productivity and frame the discussion in relation to labor output or labor costs per “unit” produced. This relationship between labor costs and output levels is depicted in the chart above (Unit Labor Costs (ULC): Nonfarm Business).

Note the red line that shows the annual change (versus the blue bars, which are quarterly changes) in unit labor costs, or the costs of labor in producing goods and services. Note the significant increase in labor costs in relation to production in 2022 and the very significant decline in unit labor costs, which translates to a large increase in labor productivity. On a year-over-year basis, unit labor costs are now about zero, as labor productivity growth is keeping up with rising labor costs. This is the first time we have witnessed that level of increase in productivity in 10 years.

Growth in labor productivity growth rates is the magic elixir of higher income flows, which eventually turns into higher levels of societal wealth. Higher levels of worker productivity also allow inflation pressures to remain low and employers to raise wages without harming profit margins dramatically. Low inflation rates should be aided by ongoing improvements in unit labor costs. I suspect the noted trend should continue as we move into 2025.

Core Case Stated

So, there you have it. We suggest that the U.S. economy should see slow but sustainable growth in 2025 coupled with declining interest rates and a tame inflation profile. Today’s outline is our best guess or core case as to the overall macroeconomic environment that we suggest may unfold in 2025. The economic outlook will become a little clearer following the upcoming election.

Will we see a recession unfold in 2025, dashing the positively biased outcome outlined above? Perhaps. However, recessions are born out of imbalances, economic friction, surprises and tight monetary policies. The major imbalance the nation’s economy (and investors) faces is the federal government deficit, federal business regulations and the seemingly ever-expanding influence the government exerts on daily business and economic life.

Next month, we will outline risks to the core case and offer alternatives to it.

Sources:

1-4Bureau of Economic Analysis, U.S. Department of Commerce

This commentary is provided for informational and educational purposes only. As such, the information contained herein is not intended and should not be construed as individualized advice or recommendation of any kind.

The opinions and forward-looking statements expressed herein are not guarantees of any future performance and actual results or developments may differ materially from those projected. The information provided herein is believed to be reliable, but we do not guarantee accuracy, timeliness, or completeness. It is provided “as is” without any express or implied warranties.

There is no assurance that any investment, plan, or strategy will be successful. Investing involves risk, including the possible loss of principal. Past performance does not guarantee future results, and nothing herein should be interpreted as an indication of future performance. Please consult your financial professional before making any investment or financial decisions.

Mariner is the marketing name for the financial services businesses of Mariner Wealth Advisors, LLC and its subsidiaries. Investment advisory services are provided through the brands Mariner Wealth, Mariner Independent, Mariner Institutional, Mariner Ultra, and Mariner Workplace, each of which is a business name of the registered investment advisory entities of Mariner. For additional information about each of the registered investment advisory entities of Mariner, including fees and services, please contact Mariner or refer to each entity’s Form ADV Part 2A, which is available on the Investment Adviser Public Disclosure website. Registration of an investment adviser does not imply a certain level of skill or training.